Machines - Robots - Automobiles - Energy - Never Ending Technology - Power - Go Green - Pumps - Compressors - Power Plant - CAD - Cooling Tower - Oil & Gas - Heat Exchangers - Interview - Mock campus - Ship - Materials ...

Clean Energy Technologies

Back-Pressure Power Recovery

· Natural gas Pressure Recovery Turbines

· Pressure Power Recovery

· Organic Rankine Cycle

· Flare Gas Recovery

· Advanced Cogeneration – Iron & Steel Industry

· Cheng Cycle or Steam Injected Gas Turbine

· Gasturbine Process heater

· Gas Turbine – Drying

· Fuels Cells in the Chlorine-Alkaline Industry

· Black Liquor Gasification

· Residue Gasification – Petroleum Refining

· Residue Gasification – Other Industries

· VOC Control (EPSI)

· Anaerobic Digestion - Agriculture

· Anaerobic Digestion - Municipal Wastewater

·

Anaerobic

Digestion - Industrial Wastewater

Landfill

Gas

District Heating – Back-Pressure Power Recovery

District Heating is an established, mature technology, with several large steam systems

having been installed in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The principle of district

heat systems is that a central plant produces steam or high-pressure hot water for

distribution to commercial and large residential customers. As a result of lower capital

and energy costs, modern district heating systems use high-pressure hot water almost

exclusively. Older systems continue to use steam, and are largely locked into this

distribution method because hot water systems require a new set of distribution pipes, and

cannot run the existing steam powered absorption chillers. A typical steam based system

starts with some form of cogeneration of steam and electricity, with the resulting steam at

50 to 200 pounds per square inch gauge (psig) (0.4-1.4 bar). This steam then flows

through the distribution system to locations up to 3 miles away. When the steam enters

the building, the pressure is reduced to 10-15 psig (70-100 mbar) to minimize the stresses

on the building’s internal system. Once the heat has been extracted, the condensate is

returned to the steam generating plant. Typically, the pressure reduction at the building is

accomplished through a pressure reduction valve (PRV). These valves do not recover the

energy embodied in the pressure drop between 150 (1 bar) and 15 psig (100 mbar). This

energy could be recovered by using a micro scale back-pressure steam turbine. Several

manufactures produce these turbine sets, such as Turbosteam and Dresser-Rand.

Industry – Back-Pressure Power Recovery

Industry consumed at least 3,635 TBtu (3.8 EJ) of fuels in 1998 to generate steam. The

steam is generated at high pressures, but often the pressure is reduced to allow the steam

to be used by different processes. Industrial steam distribution pressures are higher than

district energy applications. Steam is generated at a few bar while pressure is reduced for

distribution (high pressure distribution pressures of 800 psig (5.5 bar) are not

uncommon). This steam then flows through the distribution system within the plant. The

pressure is typically reduced to 50 to 200 psig (0.4 – 1.4 bar) and even as low as 10-15

psig (70-100 mbar) for small space heating applications. Once the heat has been

extracted, the condensate is often returned to the steam generating plant. Typically, the

pressure reduction is accomplished through a pressure reduction valve (PRV). These

valves do not recover the energy embodied in the pressure drop. This energy could be

recovered by using a micro scale back-pressure steam turbine.

Natural gas Pressure Recovery Turbines

While it is necessary to transport natural gas at high pressures, end-users

require gas delivery at only a fraction of main pipeline pressure. Pressure is generally

reduced with a regulator, a valve that controls outlet pressure. Expansion turbines can

replace regulators. These turbines offer a way to capture some of the energy contained in

high-pressure gas by harnessing the energy released as gas expands to low pressure, thus

generating electricity. Expansion turbines use the pressure drop when natural gas from

high-pressure pipelines is decompressed for local networks to generate power. Expansion

turbines (also known as generator loaded expanders) actually serve as a form of power

recovery, utilizing otherwise unused pressure in the natural gas grid. Expansion turbines

are generally installed in parallel with the regulators that traditionally reduce pressure in

gas lines. The drop in pressure in the expansion cycle causes a drop in temperature.

While turbines can be built to withstand cold temperatures, most valve and pipeline

specifications do not allow temperatures below –15°C (5°F). In addition, gas can become

wet at low temperatures, as heavy hydrocarbons in the gas condense. Expansion

necessitates heating the gas just before or after expansion. The heating is generally

performed with either a combined heat and power (CHP) unit, or a nearby source of

waste heat. We focus on locations with sufficient low-temperature waste heat available to

preheat the gas, such as power stations (sites where much natural gas is consumed).

Also, industrial sites such as steel mills have opportunities to recycle energy

economically because of easier electrical connections and heat rejection.

Pressure Power Recovery

Various processes run at elevated pressures, enabling the opportunity for power recovery

from the pressure in the flue gas. The major current application for power recovery in the

petroleum refining industry is the fluid catalytic cracker (FCC). However, power

recovery can also be applied to hydrocrackers (petroleum refining), dual-pressure nitric

acid plants (chemical industry) and pressurized blast furnaces (iron and steel industry).

Gas holders are another simple and cost effective technology. The volume of gas on site

changes rapidly several times per hour. Boilers and steam turbines cannot change

production levels rapidly enough to capture the surges, requiring the gas to be flared.

Gas holders are big bags supported by a large steel cylinder and can absorb the rapid gas

volume changes, then average out boiler fired gas and eliminate flares.

Refining. Power recovery applications for FCC are characterized by high volumes of

high temperature gases at relatively low pressures, while operating continuously over

long periods of time between maintenance stops (> 32,000 hours). The turbine is used to

drive the FCC compressor or for to generate (additional) power (Worrell and Galitsky,

2005). There is wide and long-term experience with power recovery turbines for FCC

applications. Various designs are marketed, and newer designs tend to be more efficient

in power recovery. Many refineries in the US and around the world have installed

recovery turbines. Valero has recently upgraded the turbo expanders at its Houston and

Corpus Christi (Texas) and Wilmington (California) refineries. Valero’s Houston

Refinery replaced an older power recovery turbine to enable increased blower capacity to

allow an expansion of the FCC. At the Houston refinery the rerating of the FCC power

recovery train led to power savings of 22 MW (Valero, 2003), and will export additional

power (up to 4 MW) to the grid.

Power recovery turbines can also be applied at hydrocrackers. Power can be recovered

from the pressure difference between the reactor and fractionation stages of the process.

In 1993 the Total refinery in Vlissingen, The Netherlands, installed a 910 kW power

recovery turbine to replace the throttle at its hydrocracker (45,653 barrel/calendar day).

The cracker operates at 160 bar. The power recovery turbine produces about 7.3

GWh/year.

Based on the installation at Valero we estimate the total potential for power export in all

U.S. refineries at 170 MW. Our analysis indicates that 50% of the potential FCC capacity

can install power recovery turbines cost-effectively. This will produce 722 GWh of

power annually (8500 hours/year). Based on the installed hydrocracker capacity of

1.47·106 barrels/day, we estimate the additional potential for power recovery for

hydrocrackers at 29 MW, producing 247 GWh/year.

Chemicals. Nitric acid is produced through the controlled combustion of ammonia. The

modern process variant is the dual-pressure process, allowing power recovery between

the two reactors. Also, the single-stage high-pressure process allows for power recovery.

The recovered power can be used to power the compressors or for power generation. The

10

U.S. chemical industry produces about 7 million metric tons (Mt) of nitric acid per year

at multiple locations. Expanders can also be used in the production of ethylene oxide. The

expanders are often used to drive the compressor. Hence, we assume that no additional

power is generated, although the expander may reduce the need for a steam turbine or

electrically driven compressor, potentially reducing electricity use onsite of the chemical

plant.

Iron & Steel. Top pressure recovery turbines are used to recover the pressure in the blast

furnace.1 Although the pressure difference is low, the large gas volumes make the recovery

economically feasible. The pressure difference is used to produce 15-40 kWh/t hot metal

(Stelco, 1993). Turbines are installed at blast furnaces worldwide, especially in areas where

electricity prices are relatively high (e.g. Western Europe, Japan). The standard turbine has

a wet gas cleanup system. The top gas pressure in the U.S. is generally too low for

economic power recovery. A few large blast furnaces (representing about 11 Mt of

production) have sufficiently high pressure (Worrell et al., 1999). We estimate the technical

potential at 325 GWh, or about 40 MW capacity.

Organic Rankine Cycle

Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) is the same process as a steam turbine system with the

driving fluid being an organic fluid instead of steam. The standard Rankine Cycle

requires superheated steam above 600°C. ORC can work with lower temperature fluids in

the range of 100°C to 400°C. Lower temperature operation uses lower quality heat, often

residual, that would otherwise be wasted to generate electricity. The efficiency is around

10-20% depending on the temperature of the fluid. Fluids used in ORC are CFCs, Freon,

isopentane and ammonia. The range for heat recovery capacities of ORC turbines is 400

to 1500 kW. A proposed large ORC project in The Netherlands had a simple payback of

6.5 years and capital costs of about $950 per kW.

Flare Gas Recovery

In oil and gas production methane-containing gases are vented and flared throughout the

production cycle. In natural gas production methane is vented and leaking from storage

facilities and pipelines. In oil production, methane is vented from oil tanks and may leak

from refineries. Furthermore, oil refineries flare methane and hydrocarbon containing

gases. Flares are used for both background and upset (emergency) use. In all cases the

methane can be recovered and used for local power production. The recovery and use for

power generation will not only offset power generation but also reduce methane

emissions, a potent greenhouse gas, leading to double benefits. Companies like BP have

shown that it is possible to reduce the leaks and recover methane from oil and gas

production facilities at a profit

Advanced Cogeneration – Iron & Steel Industry

All plants and sites that need electricity and heat (i.e. steam) in the steel industry are

excellent candidates for cogeneration. Conventional cogeneration uses a steam boiler and

steam turbine (back pressure turbine) to generate electricity. Steam systems generally

have a low efficiency and high investment costs. Current steam turbine systems use the

waste fuels, e.g. at Inland Steel and US Steel Gary Works. Modern cogeneration units are

gas turbine based, using either a simple cycle system (gas turbine with waste heat

recovery boiler), or a combined cycle integrating a gas turbine with a steam cycle for

larger systems.

Integrated steel plants produce significant levels of off-gases (coke oven gas, blast

furnace gas, and basic oxygen furnace-gas). Specially adapted turbines can burn these

low calorific value gases at electrical generation efficiencies of 45% (LHV) but internal

compressor loads reduce these efficiencies to 33% (Mitsubishi, 1993). Mitsubishi Heavy

Industries has developed such a turbine and it is now used in several integrated steel

plants around the world, e.g. Kawasaki Chiba Works (Japan) (Takano et al., 1989) and

Corus (IJmuiden, The Netherlands) (Anon., 1997). These systems have low NOx

emissions (20 ppm) (Mitsubishi, 1993).

Cheng Cycle or Steam Injected Gas Turbine

This type of turbine uses the exhaust heat from a combustion turbine to turn water into

high pressure steam. This steam is then fed back into the combustion chamber to mix

with the combustion gas. This technology is also known as a steam injected gas turbine

(STIG). The advantages of this system are (Willis and Scott 2000):

· Added mass flow of steam through turbine increases power by about 33%;

· Simplifies the machinery involved by eliminating the additional turbine and

equipment used in combined cycle gas turbine;

· Steam is cool compared to combustion gasses helping to cool the turbine interior;

· Reaches full output more quickly than combined-cycle unit;

· Applicable for DER applications due to smaller equipment size.

Additional advantages are that the amounts of power and thermal energy produced by a

turbine can be adjusted to meet current power and thermal energy (steam) loads. If steam

loads are reduced then the steam can be used for power generation, increasing output and

efficiency (Ganapathy 2003).

Drawbacks include the additional complexity of the turbine’s design. Additional

attention to the details of the turbine’s design and materials are needed during the design

phase. This may result in a higher capital cost for the turbine compared to traditional

models.

Combined cycles (combining a gas turbine and a back-pressure steam turbine) offer

flexibility for power and steam production at larger sites, and potentially at smaller sites

as well. STIG can absorb excess steam, e.g. due to seasonal reduced heating needs, to

boost power production by injecting the steam in the turbine. The size of typical STIGs

starts around 5 MWe. STIGs are found in various industries and applications, especially

in Japan and Europe, as well as in the U.S. International Power Technology (CA), for

example, installed a STIG at Sunkist Growers in Ontario (CA) in 1985.

Gasturbine Process heater

Modern turbine designs allow higher inlet and outlet temperatures. The makes it possible

to use the flue gas of the turbine to heat a reactor in the chemical and petroleum refining

industries. One option is the so-called “re-powering” option. In this option, the furnace is

not modified, but the combustion air fans in the furnace are replaced by a gas turbine.

The exhaust gases still contain a considerable amount of oxygen, and can thus be used as

combustion air for the furnaces. The gas turbine can deliver up to 20% of the furnace

heat. The re-powering option is used by a few plants around the world. Another option,

with a larger CHP potential and associated energy savings, is “high-temperature CHP.”

In this case, the flue gases of a CHP plant are used to heat the input of a furnace. Zollar

(2002) discusses various applications in the chemical and refinery industries. The study

found a total potential of 44 GW. The major candidate processes are atmospheric

distillation, coking and hydrotreating in petroleum refineries and ethylene and ammonia

manufacture in the chemical industry. The simple payback period is estimated at 3 to 5

years, depending on the electricity costs. The additional investments compared to a

traditional furnace were estimated at 630 $/kW (1997) (Worrell et al., 1997; Onsite,

2000). Excessive costs for adaptation of an existing furnace are additional to the given

investment costs. This cycle has nearly 100% efficiency since the fuel is either converted

into power or waste heat, all of which is used in the boiler. This greatly influences power

generation costs and reduces sensitivity to fuel price

Gas Turbine – Drying

CHP Integration allows increased use of CHP in industry by using the heat in more

efficient ways. This can be done by using the heat as a process input for drying. The

fluegas of a turbine can often be used directly in a drier. This option has been used

successfully for the drying of minerals as well as food products. Although NOx emissions

of gas turbines vary widely, tests in The Netherlands have shown that, depending on the

type of gas turbine selected, the flue gases do not negatively affect the drying air and

product quality(Buijze, 1998). To allow continuous operation, bypass of the gas turbines

makes it possible to maintain the turbine and run the drying process (Buijze, 1998). A

cement plant in Rozenburg, The Netherlands, uses a standard industrial gas turbine to

generate power and to dry the blast furnace slags used in cement making. The Kambalda

nickel mine in Australia uses four gas turbines of 42 MW each to dry nickel concentrate.

The mine currently produces around 300,000 tons per year, saving 0.9 GJ/ton (0.77

MBtu/short ton) of concentrate. Another project in The Netherlands demonstrated the use

of the flue gases from a gas turbine to dry protein rich cattle feed by-product. The excess

flue gas is mixed with air and used directly for the drying process.

Fuels Cells in the Chlorine-Alkaline Industry

Fuel cells generate direct current electricity and heat by combining fuel and oxygen in an

electrochemical reaction. This technology avoids the intermediate combustion step and

boiling water associated with Rankine cycle technologies, or efficiency losses associated

with gas turbine technologies. Fuel to electricity conversion efficiencies can theoretically

reach 80-83% for low temperature fuel cell stacks and 73-78% for high temperature

stacks. In practice, efficiencies of 50-60% are achieved with hydrogen fuel cells while

efficiencies of 42-65% are achievable with natural gas as a fuel (Martin et al., 2000). The

main fuel cell types for industrial CHP applications are phosphoric acid (PAFC), molten

carbonate (MCFC) and solid oxide (SOFC). Proton exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cells

are less suitable for cogeneration as they only produce hot water as byproduct. PAFC

efficiencies are limited and the corrosive nature of the process reduces the economic

attractiveness of the technology. Hence, MCFC and SOFC offer the most potential for

industrial applications.

Black Liquor Gasification

In standard integrated Kraft mills, the spent liquor produced from de-lignifying wood

chips (called black liquor) is normally burned in a large recovery boiler in which the

black liquor combustion is used to recover the chemicals used in the delignification

process. Because of the relatively high water content of the black liquor fuel, the

efficiency of existing recovery boilers is limited. Gasification allows not only the

efficient use of black liquor, but also of other biomass fuels such as bark and felling rests

to generate a synthesis gas that after cleaning is combusted in a gas turbine or combined

cycle with a high electrical efficiency. This increases the electricity production within the

pulp mill. The technology is called black liquor gasification-combined cycle (BLGCC).

The black liquor gasifier technology will produce a surplus of energy from the pulp

process and opens the possibility to generate several different energy products for

external use, i.e. electricity, heat and fuels. Gasifiers can use air or pure oxygen to

provide the oxygen needed for the chemical conversions. We assume a (more expensive)

oxygen-blown gasifier. The richer synthesis gas produced in an oxygen-blown gasifier

allows easier combustion in a gas turbine. Furthermore, the process provides a natural

separation of sulfur from sodium is provided that allows for advanced pulping, making it

possible to enhance pulp productivity

Residue Gasification – Petroleum Refining

Because of the growing demand for lighter products and increased use of conversion

processes to process a ‘heavier’ crude, refineries will have to manage an increasing

stream of heavy bottoms and residues. Gasification of the heavy fractions and coke to

produce synthesis gas can help to efficiently remove these by-products. The state-of-theart

gasification processes combine the heavy by-products with oxygen at high

temperature in an entrained bed gasifier. The synthesis gas can be used as feedstock for

chemical processes, hydrogen production and generation of power in an Integrated

Gasifier Combined Cycle (IGCC). Entrained bed IGCC technology was originally

developed for refinery applications, but is also used for the gasification of coal. Hence,

the major gasification technology developers were oil companies like Shell and Texaco.

The technology was first applied by European refineries due to the characteristics of the

operations in Europe (e.g., coke was often used onsite). IGCC is used by the Shell

refinery in Pernis (The Netherlands) to treat residues from the hydrocracker and other

residues to generate 110 MWe of power and 285 metric tons of hydrogen for the refinery.

Residue Gasification – Other Industries

Various industries produce low-grade fuels as a by-product of the production process.

Currently, these low-grade fuels are combusted in boilers to generate steam or heat, or

disposed of through landfilling. Often, this results in relatively less efficient use.

Gasification offers opportunities to increase the efficiency of using low-grade fuels. In

gasification, the hydrocarbon feedstock is heated in an environment with limited oxygen.

The hydrocarbons react to form synthesis gas, a mixture of mainly carbon monoxide and

hydrogen. The synthesis gas can be used in more efficient applications like gas turbinebased

power generation or as a chemical feedstock. The technology not only allows the

efficient use of by-products and wastes, it also allows low-cost gas cleanup (when

compared to flue gas treatment). Various industries are pursuing the development of

gasification technology, and are at different stages of development. Furthermore,

gasification technology can also lead to more efficient and cleaner use of coal, biomass

and wastes for power generation. Besides the pulp and paper and petroleum refining

industries other industries with sufficient production of by-products that can be gasified

are found in the food industry (e.g. bagasse in the sugar industry, nutshells, rice husk).

The technology can also be used to process municipal solid waste with a higher

efficiency than offered by incineration

VOC Control (EPSI)

In many plants VOCs are generated. VOCs contribute to ozone formation and VOC

controls are installed by virtually at any source of VOC emissions. In small-scale systems

carbon filters can be used to capture VOCs. In large-scale systems, generally regenerative

thermal oxidizers (RTO) are used. In a RTO the VOC-containing flue gas (e.g. from a

paint booth) is mixed with natural gas to a combustible mixture. The mixture is

combusted in the RTO and the VOCs are destroyed.

Environmental and Power Systems International (EPSI) has developed an alternative

pollution control technology for handling VOC emissions. The technology has the ability

to generate electricity and useful thermal heat with a gas turbine, using the VOCcontaining

gases enriched with natural gas. The EPSI system is an alternative VOC

abatement technology to RTOs with the following advantages over standard RTOs (GTI

2003):

· Shorter initial cold start-up time (5 minutes versus 1 to 8 hours);

· Recoverable heat for use by end-user (RTOs use their heat in the VOC abatement

process);

· Electrical power generation;

· Higher combustion temperature (which in combination with high residence time,

assures more complete destruction of VOC);

· Smaller equipment footprint;

· Lower major overhaul cost.

Anaerobic Digestion - Agriculture

Biogas systems are a waste management technique that can provide multiple benefits:

· removal of manure waste;

· reduction of odor;

· reducing disposal truck traffic and costs;

· reduction in spreading disposal costs;

· pathogen control and destruction, and;

· protection of groundwater.

Furthermore biogas digester systems can generate electricity and thermal energy to serve

heating and cooling needs while providing financial profits. The byproducts of the

digester system also include high-quality compost that can be used for crop fertilizer.

Biogas systems are most suitable for farms that handle a large amount of manure as a

liquid slurry or semi-solid with little or no bedding added. The type of digester should be

matched to the type, design, and manure characteristics of the farm. There are five types

of manure collection systems characterized by the solids content: raw, liquid, slurry,

semi-solid, or solid (often left in pasture and not suitable). There are three types of

digester systems: covered lagoon (used to treat and produce biogas from liquid manure),

complete mix digester (heated engineered tanks for scraped and flushed manure), and

plug flow (treat scraped dairy manure in 11% to 13% solids range). Swine manure does

not have enough fiber to treat in plug flow digester. The products of anaerobic digestion

are biogas and effluent. The effluent needs to be stored in a suitable sized tank.

Recovered gas is 60-80% methane with heating value of 22-30 MJ (600-800 Btu/ft3)

(AgSTAR Handbook). This gas can be used to generate electricity or serve heating and

cooling loads.

Anaerobic Digestion - Municipal Wastewater

Wastewater treatment plants release biogas through the decomposition of organic matter.

The biogas (mostly methane) can be captured and used to provide energy services either

by direct heating or through the generation of electricity. Anaerobic digestion destroys

pathogens and this method is used to generate biogas in many treatment plants. Typically

the biogas is burned to produce heat to maintain the temperature of the digester process.

Excess gas is then flared (Oregon State Energy Office 2004). This process destroys

pathogens resulting in cleaner water and more benign solids.

Anaerobic Digestion - Industrial Wastewater

Industrial wastewater is typically treated by aerobic systems that remove contaminants

prior to discharging the water. These aerobic systems have a number of disadvantages

including high electricity use by the aeration blowers, production of large amounts of

sludge, and reduction of dissolved oxygen in the wastewater which is detrimental to fish

and other aquatic life. The decomposition of organic materials without oxygen results in

the production of carbon dioxide and methane from the presence of anaerobic bacteria.

This gas is called biogas and contains 50% methane (CH4) and a powerful greenhouse

gas (21 times more potent of a greenhouse gas than CO2). This process is called

anaerobic digestion and takes place in an airtight chamber called a digester. Biogas

systems are a waste management technique with numerous benefits including: lower

water treatment cost, reduction in odor, reduction in material handling and wastewater

treatment costs, and protection of local environmental groundwater and other resources.

In addition the biogas can be used as a supplemental energy source for thermal energy

loads and the generation of electricity.

Any type of biological waste from plant or animals is a potential source of biogas. Some

example industries include: pharmaceutical fermentation, pulp and paper wastewaters,

fuel ethanol facility, brewery and yeast fermentation wastewater, coal conversion

wastewater. Anaerobic digester biogas is comprised of methane (50%-80%), carbon

dioxide (20%-50%), and trace levels of other gases such as hydrogen, carbon monoxide,

nitrogen, oxygen, and hydrogen sulfide. The most widely used technology for anaerobic

wastewater treatment is the Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket (UASB) reactor, which

was developed in 1980 in The Netherlands. Industrial wastewater is directed up through

the UASB reactor, passing through a “blanket” that traps the sludge. Anaerobic bacteria

break down the organic compounds in the sludge, producing methane in the process. This

type of anaerobic wastewater treatment is currently used predominantly in the paper and

food industries, but some industries such as chemical and pharmaceuticals have also used

this technology and its use is growing for municipal wastewater treatment.

Landfill Gas

The decomposition of organic materials without oxygen in landfills results in the

production of carbon dioxide and methane from the presence of anaerobic bacteria. In a

non-controlled landfill, this would generate methane, a powerful greenhouse gas.

Therefore, the landfill gas is often collected and flared, in which case the energy is not

utilized. However, the gas can also be used for energy generation. The more common

uses are: fuel gas for industrial boilers and electricity generation.

At many landfills, however, the gas is not recovered or flared. There are numerous

barriers to economically utilizing landfill gas (EIA 1996): fluctuating gas prices,

technology prices and performance risks, transportation costs of energy (when

transported), air permits and changing regulations, as well as obtaining power contracts

Thermal Storage Walls

A thermal storage wall is a passive solar heating system in which the primary thermal storage medium is placed directly behind the glazings of the solar aperture. The outer surface of the massive wall is painted a dark color or coated with a selective surface to promote absorption of solar radiation. Solar radiation absorbed on the outer surface of the wall is converted to heat and conducted (or convected in the case of the water walls) to the inner surface where it is radiated and convected to the living space. Heat transfer to the living space is sometimes augmented by the addition of circulation vents placed at the top and bottom of the mass wall. These vents function in the same manner as the vents in a TAP system except that only a portion of the solar heat delivered by the system passes through the vents.

A

thermal storage wall provides an effective buffer between outside ambient

conditions and the building interior; night time heat losses are reduced during

the cold winter months, and during the summer, unwanted heat gains are limited.

This moderating effect generally enables thermal storage walls to outperform

direct gain systems. There are many types of thermal storage walls

distinguished by the type of storage medium employed.

Trombe Wall. A Trombe wall is a thermal storage wall that

employs solid, high density masonry as the primary thermal storage medium.

Appropriate thicknesses range from 6 to 18 inches depending on the solar

availability at the building site. Sunny climates require relatively thicker

walls due to the increased thermal storage requirements. The wall may be vented

or unvented. A vented wall is slightly more efficient and provides a quicker

warm up in the morning but may overheat buildings

containing

little secondary thermal storage mass in the living space.

Concrete Block Wall. Ordinarily, a thermal storage wall

would not be constructed of concrete building blocks, because solid masonry

walls have a higher heat capacity and yield better performance. However, where

concrete block buildings are very common they may offer opportunities for

passive solar retrofits. The south facing wall of a concrete block building can

be converted to a thermal storage wall by simply painting the block a dark

color and covering it with one or more layers of glazing. Walls receiving this

treatment yield a net heat gain to the building that usually covers the

retrofit costs rather quickly. The relatively low heat capacity of concrete

block walls is offset somewhat by the large amount of secondary thermal storage

mass usually available in these buildings. Concrete floor slabs and massive

partitions between zones help prevent overheating and otherwise improve the

performance of concrete block thermal storage walls. Concrete block thermal

storage walls may also be introduced during the construction of new buildings.

For new construction, however, it is advisable to take advantage of the

superior performance of solid masonry walls by filling the cores of the block

in the thermal storage wall with mortar as it is erected. This process is inexpensive

and the resulting performance increment covers the increased cost. The design

procedures developed herein are applicable to 8-inch concrete block thermal

storage walls with filled or unfilled cores.

Water Wall. Water walls are thermal storage walls that use

containers of water placed directly behind the aperture glazings as the thermal

storage medium. The advantage over masonry walls is that water has a volumetric

heat capacity about twice that of high density concrete; it is therefore

possible to achieve the same heat

capacity available in a Trombe wall while using only half the

space. Furthermore, a water

wall can be

effective at much higher heat capacities than a Trombe wall because natural

convection within the container leads to an nearly isothermal condition that

utilizes all of the water regardless of the wall thickness. The high thermal

storage capacity of water walls makes them especially appropriate in climates

that have a lot of sunshine.

Heat transfer fluid contained in the collector loop

Heat transfer fluid contained in the collector loop are :

WATER.

As a

heat transfer fluid, good quality water offers many advantages. It

is

safe, non-toxic, chemically stable, inexpensive, and a good heat transfer

medium.

Two

drawbacks include a relatively high freezing point and a low boiling point.

Excessive

scaling may occur if poor quality water is used.

GLYCOLS.

Propylene

or ethylene glycol is often mixed with water to form an

antifreeze

solution. Propylene glycol has the distinct advantage of being nontoxic,

whereas

ethylene glycol is toxic and extreme caution must be used to ensure that it is

isolated from any potable water. For this reason, uninhibited USP/food-grade

propylene glycol and water solution will be specified for any solar preheat

system that requires an antifreeze solution.

Solar thermal energy collection system

A solar thermal energy collection system is defined as a set of equipment that intercepts incident solar radiation and stores it as useful thermal energy to offset or eliminate the need for fossil fuel consumption. Four basic functions are performed by a typical solar system.

COLLECTOR

SUB-SYSTEM. The

collector sub-system intercepts incident solar

radiation

and transfers it as thermal energy to a working fluid. It is defined as the

solar

collector,

the hardware necessary to support the solar collector, and all interconnecting

piping

and fittings required on the exterior of the building housing the system.

STORAGE

SUB-SYSTEM. The

storage sub-system retains collected thermal

energy

for later use by the process load. It is defined as the storage tank and its

fittings

as

well as other necessary supports.

TRANSPORT

SUB-SYSTEM. The

transport sub-system delivers energy from the

collectors

to storage. This sub-system is defined to include the heat transfer (or

working)

fluid, pump(s), the remaining system piping and fittings, an expansion tank,

and

a heat exchanger (if required).

CONTROL

SUB-SYSTEM. The

control sub-system must first determine when

enough

energy is available for collection. It must then activate the entire system to

collect

this energy until it is no longer available as a net energy gain. The control

subsystem

thus consists of electronic temperature sensors, a main controlling unit that

analyzes

the data available from the temperature sensors, and the particular control

strategy

used by the controller.

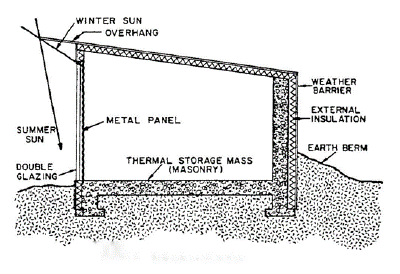

Sunspaces

There are many possible configurations for a sunspace but all of them share certain basic characteristics. Sunlight enters the sunspace through south facing glazing that may be vertical or inclined or a combination of the two and is absorbed primarily on mass surfaces within the enclosure; the mass may be masonry or water in appropriate containers and is generally located along the north wall and in the floor. The massive elements provide thermal storage that moderates the temperature in the enclosure and the rate of heat delivery to the living space located behind the north wall. Operable windows and circulation vents in the north wall provide for heat transfer by thermal convection from the sunspace to the living space. The north wall may be an insulated stud wall placed behind containers of water or a masonry wall through which some of the heat in the sunspace is delivered to the building interior by thermal conduction as occurs in a Trombe wall. A sunspace may be semi-enclosed by the main structure such that only the south facing aperture is exposed to ambient air, or may be simply attached to the main structure along the north wall of the sunroom, leaving the end walls exposed.

COLLECTOR EFFICIENCY AND PERFORMANCE

Collector efficiency is defined as the fraction of solar energy

incident upon the face of the collector that is removed by the fluid circulating through the collector. Several parameters are defined as follows:

Ti = heat transfer fluid inlet temperature

Ta = ambient air temperature

I = solar irradiance on the collector

Ac = solar collector surface area

FR = collector heat removal factor, a dimensionless parameter describing the ratio

of actual energy gained by the collector to that which would be gained, in

the limit, as the absorber plate temperature approaches the fluid inlet

temperature. This value is similar to a conventional heat exchanger's

effectiveness.

UL = overall heat loss coefficient. This factor describes the cumulative heat

transfer between the collector and the ambient surroundings.

t = transmittance of the glazing.

a = absorption coefficient for the absorber plate. Note that this value varies with

wavelength. A selective surface is one that absorbs short wavelength solar

radiation very well while emitting longer wavelength thermal radiation poorly.

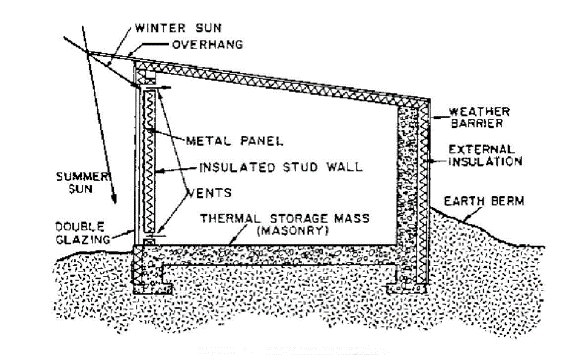

Thermosiphoning Air Panels

Thermosiphoning Air Panels. Thermosiphoning air panels (TAPs) are also appropriate for use on metal buildings either as retrofits or in new construction. Two configurations occur in practice and the first, which is referred to as a frontflow system. Again there are one or more glazing layers over an absorbing metal surface but, in this case, the metal panel is insulated on the back side. Heat

transfer

to the interior occurs via circulation vents cut through the metal panel and

its insulation at the upper and lower extremes. Solar radiation absorbed on the

the outer surface of the panel is converted to heat and convected to the

adjacent air which then rises due to buoyancy forces and passes through the

upper vent into the living space. The warm air leaving the gap between the

inner glazings and the absorber is replaced by cooler air from the building

interior that enters through the lower vents. In this manner, a buoyancy driven

loop is established and sustained as long as the temperature in the air gap

exceeds that in the living space. Passive backdraft dampers or manually

operated vent closures must be employed to prevent reverse circulation at

night. Backdraft dampers are usually made of a lightweight plastic material

suspended above a metal grid such that air flows freely in one direction but is

blocked should the flow attempt to reverse.

The

second type of TAP configuration is called a backflow system. In a backflow

system, the flow channel is behind the absorber plate rather than in front of

it. An insulated stud wall is constructed a few inches behind the metal panel

and vents are then cut at the top and bottom of the wall. Air in the flow

channel thus formed is heated by convection from the back of the absorber panel

and a circulation loop is established in the same manner as in a front flow

system.

TAPs have thermal storage requirements similar to those of direct gain and radiant panel systems. Generally speaking, the best performance will be obtained from passive solar systems associated with high heat capacity structures. Although a backflow TAP performs slightly better than a comparable system in the frontflow configuration, the difference is not significant and construction costs should govern any choice between the two. Both TAP configurations outperform radiant panels and direct gain systems with comparable glazings and thermal storage mass. This performance edge is due to the low aperture conductance of TAPs, which can be insulated to arbitrary levels, thereby limiting night time heat loss.

Radiant Panels for Homes

Radiant Panels

Radiant

panels are simple passive solar systems that are inexpensive and well suited as

retrofits to metal buildings. Note that the solar aperture consists of one or

more layers of glazing material placed over an uninsulated metal panel. The

metal panel would ordinarily be a part of the building shell so that a retrofit

is constructed by simply glazing an appropriate area on the south side of the

structure. Any insulation or other poorly conducting material should be removed

from the inner surface of the glazed portion of the metal panel to facilitate

heat transfer to the interior.

Solar

radiation is absorbed on the outer surface of the metal panel after passing

through the glazings. The panel becomes hot and gives up heat to the interior

by radiation and convection. Thermal mass must be included inside the building

shell as with direct gain systems. Usually, only a concrete slab will be

available before retrofitting a metal building and it may sometimes be

necessary to add water containers to achieve the desired thermal capacitance.

Radiant panels perform on a par with direct gain buildings and are likely to be

less expensive when used as retrofits to metal buildings.

Transpired collectors

Transpired collectors use solar energy to preheat ventilation (outdoor) air as it is drawn into a building. The technology is ideally suited for buildings with at least moderate ventilation requirements in sunny locations with long heating seasons. Transpired collector technology is remarkably simple. A dark, perforated metal wall is installed on the south-facing side of a building, creating approximately a 6-inch (15-cm) gap between it and the building’s structural wall. The dark colored wall acts as a large solar collector that converts solar radiation to heat. Fans associated with the building’s ventilation system mounted at the top of the wall draw outside air through the transpired collector’s perforations, and the thermal energy collected by the wall is transferred to the

air

passing through the holes. The fans then distribute the heated air into the

building through ducts mounted from the ceiling. By preheating outdoor air with

solar energy, the technology removes a substantial load from

a

building’s conventional heating system, saving energy and money.

A

transpired collector is installed on all or part of a building’s south-facing

wall, where it will receive the maximum

exposure to direct sunlight during the fall, winter, and spring. The size of

the wall varies depending on heating and airflow requirements and climate, but

in many applications, the transpired collector will cover the maximum

south-facing area available. The amount of energy and money saved by a

transpired collector depends on the type of conventional fuel being displaced,

occupant use patterns, building design, length of heating season, and the

availability of sunlight during the heating season. In general, each square

foot of transpired collector will raise the temperature of 4 cubic feet per

minute (cfm) by as much as 40°F, delivering as

much

as 240,000 Btu annually per square foot of installed collector.

In

addition to the metal sheeting that captures solar energy, the transpired

collector heating system includes air-handling and control components that

supply the solar heated air. The ventilation system, which operates

independently of a building’s existing heating system, includes a

constant-speed fan to draw air through the

transpired

collector and into the distribution duct. Engineers typically use a

3-horsepower, 32-inch blade fan with about 10,000-cfm capacity.

Source: CED Engineering

The

following are the most common transpired collector applications:

•

Manufacturing plants

•

Vehicle maintenance facilities

•

Hazardous waste storage buildings

•

Gymnasiums

•

Airplane hangars

•

Schools

•

Warehouses requiring ventilation

What

to Avoid

The

following is a list of general applications and conditions that preclude the

cost effective use of transpired collector technology:

•

Outdoor air not required

•

Shaded or insufficient south-facing wall area

•

Buildings with existing heat recovery systems

•

Locations with short heating seasons

•

Multiple-story buildings (because of possible problems with fire codes).

SOLAR COLLECTORS and TYPES

SOLAR COLLECTORS

A

solar collector is a device that absorbs direct (and in some

cases,

diffuse) radiant energy from the sun and delivers that energy to a heat

transfer

fluid.

While there are many different types of collectors, all have certain functional

components

in common. The absorber surface is designed to convert radiant energy

from

the sun to thermal energy. The fluid pathways allow the thermal energy from the

absorber

surface to be transferred efficiently to the heat transfer fluid. Some form of

insulation

is typically used to decrease thermal energy loss and allow as much of the

energy

to reach the working fluid as possible. Finally, the entire collector package

must

be

designed to withstand ambient conditions ranging from sub-zero temperatures and

high

winds to stagnation temperatures as high as 350 degrees F (177 degrees C).

COLLECTOR

TYPES. The

three major categories that have been used most

often

are flat-plate glazed collectors, unglazed collectors, and evacuated tube

collectors.

A general description of each collector type and its application is given

below.

FLAT-PLATE.

Flat-plate

solar collectors are the most common type used and

are

best suited for low temperature heating applications, such as service water and

space

heating. These collectors usually consist of four basic components: casing,

back

insulation,

absorber plate assembly, and a transparent cover. The absorber panel is a

flat

surface that is coated with a material that readily absorbs solar radiation in

the

thermal

spectrum. Some coatings, known as "selective surfaces", have the

further

advantage

of radiating very little of the absorbed energy back to the environment.

Channels

located along the surface or within the absorber plate allow the working fluid

to

circulate. Energy absorbed by the panel is carried to the load or to storage by

the

fluid.

The absorber panel is encased in a box frame equipped with insulation on the

back

and sides and one or two transparent covers (glazing) on the front side. The

glazing

allows solar radiation into the collector while reducing convective energy

losses

from

the hot absorber plate to the environment. Similarly, back insulation is used

to

reduce

conductive energy loss from the absorber plate through the back of the

collector.

UNGLAZED.

Unglazed

collectors are the least complex collector type and

consist

of an absorber plate through which water circulates. This plate has no glazing

or

back

insulation. These collectors are often made of extruded plastic because they

are

designed

to operate at relatively low temperatures. Since they are not thermally

protected,

these collectors should be operated only in warm environments where lower

thermal

losses will occur. Swimming pool heating is the most common use of unglazed

collectors.

EVACUATED

TUBE. Evacuated

tube collectors are best suited for higher

temperature

applications, such as those required by space cooling equipment or for

higher

temperature industrial process water heating. Convective losses to the

environment

are decreased in this type of collector by encapsulating the absorber and fluid

path within a glass tube that is kept at a vacuum. Tracking mechanisms and/or

parabolic solar concentrating devices (simple or compound) are often used,

resulting in somewhat higher equipment costs.

COLLECTOR ENERGY BALANCE.

The collector parameters described

above

allow an energy balance to be expressed as:

Energy

Collected = Solar Energy Absorbed - Thermal Energy Losses to the

Environment

The

energy balance can be written in a simple equation form using the efficiency

parameters

described above:

Energy

Collected = (FRta)(I)(Ac) - (FRUL)(Ac)(Ti - Ta) (Eq. 1)

Equation

1 shows that heat losses to the environment are subtracted from the net solar

radiation

transmitted into, and absorbed by, the collector. Assuming that the efficiency

parameters

are fixed for a given collector model, the main factors that affect the amount

of

energy collected are I, Ti, and Ta. The geographical

location and the season dictate

the

weather variables I and Ta. The type of process

load and system configuration

determines

the relative circulation fluid temperature, Ti.

Typical

collector efficiency curve